Showing posts with label BrCommw. Show all posts

Showing posts with label BrCommw. Show all posts

Monday, April 22, 2024

Saturday, May 30, 2020

1848 European Tensions, WW1, Versailles

Versailles Treaty - Hitler’s Rise to Power - Ghost > .

1919-11-19: United States Senate votes to reject Treaty of Versailles -HiPo > .

1919-11-19: United States Senate votes to reject Treaty of Versailles -HiPo > .

However, a major obstacle to the treaty's ratification was Wilson's strained working relationship with Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, the influential chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Lodge, a prominent Republican, had fundamental disagreements with Wilson on key treaty provisions.

Article X of the Covenant of the League of Nations represented Wilson's unshakable belief in collective security. Lodge and his Republican counterparts, however, saw it as a threat to American sovereignty. Republicans preferred unilateral action, asserting that America should independently determine its involvement in global conflicts. Wilson was aiming for international cooperation, but many Republicans prioritized safeguarding American interests.

Wilson embarked on a nationwide tour to secure public support for the treaty, but his efforts were in vain. Lodge and Senate Republicans proposed amendments and, on November 19, 1919 the Senate voted down the Treaty of Versailles by 55 in favour to 39, falling short of the required two-thirds majority. It was the first time the Senate had rejected a peace treaty.

The rejection had profound consequences. While it signalled a definitive adoption of isolationism in American foreign policy, the absence of the United States from the League of Nations undermined the organisation's effectiveness from the outset.

Sunday, July 28, 2019

● Acts, Charters, Treaties - post WW1

Armistice

Defence Regulations ..

NSA - National Service Act ..

Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 ..

Treachery Act 1940 ..

Britain-USA

41-8-14 Atlantic Charter ..

Lend-Lease Act 41-3-11 ..

Germany

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact - 39-8-23 to 41-6-22 ..

Germany-USSR

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact - 39-8-23 to 41-6-22 ..

41-8-14 Atlantic Charter ..

Lend-Lease Act 41-3-11 ..

Germany

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact - 39-8-23 to 41-6-22 ..

Germany-USSR

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact - 39-8-23 to 41-6-22 ..

USA

Thursday, March 28, 2019

Monday, February 25, 2019

44-6-6 D-Day - Overlord, Neptune

D-Day innovations ..

D-Day - Overlord & Neptune > .

25-6-6 Operation Titanic: 400 Dummies Duped Germans on D-Day - T&P > .

24-6-4 D-Day Shipping: Battle of Atlantic, Liberty Ships, LSTs - Shipping > .

Lies and Deceptions that made D-Day possible - IWM > .

D-Day - June 6, 1944 - anffyddiaeth >> .

British Army in Europe 44-45 >> .

D-Day - The German Naval Counterattack - mfp > .

British Army in Europe 44-45 >> .

D-Day - The German Naval Counterattack - mfp > .

D-Day - June 6, 1944 - anffyddiaeth >> .

Allied Controlled Territory after Invasion of Normandy, June 6, '44 - Aug 21, '44 > .

D-Day Logistics - Why Did The Allies Pick Normandy? > .

German Defense from Norway to Greece > .

On D-Day what did the Germans know? > .

D-Day - The German Naval Counterattack - mfp > .

D-Day at Lepe - New Forest History Hits - New Forest National Park Authority > .

New Forest in WW2

New Forest Remembers World War I & II - New Forest National Park Authority >> .

44-6-6 D-Day landings - AFPU ..

D-Day Logistics - Why Did The Allies Pick Normandy? > .

German Defense from Norway to Greece > .

On D-Day what did the Germans know? > .

D-Day - The German Naval Counterattack - mfp > .

D-Day at Lepe - New Forest History Hits - New Forest National Park Authority > .

New Forest in WW2

New Forest Remembers World War I & II - New Forest National Park Authority >> .

44-6-6 D-Day landings - AFPU ..

Saturday, February 16, 2019

Malta - Siege of Malta

.

Surviving The Siege Of Malta - time > .Malta - History, Geography, Economy and Culture - Geodiode > .

40-7-31 Operation Hurry 40-8-4 > .HMS Indomitable - "Sweepers, Man Your Brooms." - Skynea > .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Hurry .

41-1 Operation Excess - Luftwaffe attacks Malta > .

41-1 Operation Excess - Luftwaffe attacks Malta > .

HMS Illustrious and Operation Excess - Fliegerkorps X - Drach > .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Excess .

42-8-3 Operation Pedestal 42-8-15 > .

Operation Pedestal: The Convoy That Saved Malta > .

Operation Pedestal: The Convoy That Saved Malta > .

Indomitable - WoW > .

Operation Pedestal: HMS Indomitable bombed > .

Stuka pilot interview 47: Attack on HMS Indomitable August 1942 > .

The Only Country That Has Been Awarded A George Cross > .

Operation Pedestal: HMS Indomitable bombed > .

Stuka pilot interview 47: Attack on HMS Indomitable August 1942 > .

This Tiny Island Was Key for Allied Forces to Secure North Africa > .

SS Ohio and the Siege of Malta (Pedestal) > .

Mediterranean Theatre & Malta - 42-4-3 - WW2 > .

Operation Pedestal: The Convoy That Saved Malta > .

Operation Pedestal: HMS Indomitable bombed > .

Malta bombing

https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-grand-opera-house-bombed-to-ruins-by-the-luftwaffe

The Battle for Malta

Caught in a struggle between Britain and Germany to control the Mediterranean, Malta became the most bombed place on Earth. Beyond unimaginable austerity, the island was close to starvation by the summer of 1942, and the magnitude of the attacks reflected the importance of its strategic position. Like ants, the Maltese were forced to move by their thousands into man made caves and tunnels carved in island’s limestone. Historian James Holland presents a fresh analysis of this vicious battle and argues that Malta’s offensive role has been underplayed.

Clash of Wings 5/13 The African Tutorial > .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fGiw5Lo0hxg

playlist

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtq7-dtiDy8&list=PLSawWIooz_XpVAxHUUkN42HyHUy-uYhFC .

Ġgantija & Ancient Malta ..

SS Ohio and the Siege of Malta (Pedestal) > .

Mediterranean Theatre & Malta - 42-4-3 - WW2 > .

Operation Pedestal: The Convoy That Saved Malta > .

Operation Pedestal: HMS Indomitable bombed > .

Malta bombing

https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-grand-opera-house-bombed-to-ruins-by-the-luftwaffe

Caught in a struggle between Britain and Germany to control the Mediterranean, Malta became the most bombed place on Earth. Beyond unimaginable austerity, the island was close to starvation by the summer of 1942, and the magnitude of the attacks reflected the importance of its strategic position. Like ants, the Maltese were forced to move by their thousands into man made caves and tunnels carved in island’s limestone. Historian James Holland presents a fresh analysis of this vicious battle and argues that Malta’s offensive role has been underplayed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fGiw5Lo0hxg

playlist

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtq7-dtiDy8&list=PLSawWIooz_XpVAxHUUkN42HyHUy-uYhFC .

Ġgantija & Ancient Malta ..

Monday, January 28, 2019

ANZACs

1939-45 [Australia at War - Women's Status Changes] - Free > .

AAMWS - AWAS - AWLA - WAAAF - WRANS ..

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Army_during_World_War_II .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_history_of_Australia_during_World_War_II .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attacks_on_Australia_during_World_War_II .

http://www.awmlondon.gov.au/australians-in-wwii .

https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/history/conflicts/australia-and-second-world-war .

https://www.britannica.com/place/Australia/World-War-II .

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/war-articles/life-australia-world-war-two.html .

https://ww2db.com/country/australia .

https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Brisbane .

Full History of Australia - Doc - FoL > .

Army - BEF | BRE

.

How BRITISH Infantry Squads Evolved in 100 Years - Battle > .

Army Units & Sizes

http://secondworldwar.co.uk/index.php/army-sizes-a-ranks/86-army-units-a-sizes

The British Army consists of the General Staff and the deployable Field Army and the Regional Forces that support them, as well as Joint elements that work with the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. The Army carries out tasks given to it by the democratically elected Government of the United Kingdom (UK).

http://www.army.mod.uk/structure/structure.aspx

http://www.hierarchystructure.com/british-military-hierarchy/

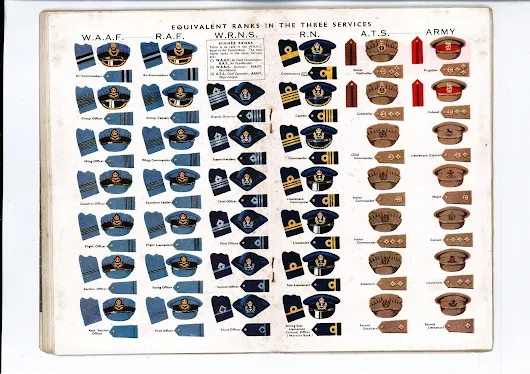

ATS-Army | WAAF-RAF | WRNS-RN |

Auxiliary vs Military Ranks WW2

https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/originals/58/cb/75/58cb75624452c757cbc659f636928d31.jpg

http://www.hierarchystructure.com/british-military-hierarchy/

http://secondworldwar.co.uk/index.php/army-sizes-a-ranks/86-army-units-a-sizes

The British Army consists of the General Staff and the deployable Field Army and the Regional Forces that support them, as well as Joint elements that work with the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. The Army carries out tasks given to it by the democratically elected Government of the United Kingdom (UK).

http://www.army.mod.uk/structure/structure.aspx

http://www.hierarchystructure.com/british-military-hierarchy/

Army Units & Sizes

Unit Name Consists of [1]: Approx Number of men:

Brigade 3 or more Battalions 1500 to 3500

Regiment[2] 2 or more Battalions 1000 to 2000

Battalion 4 or more Companies 400 to 1000

Company 2 or more Platoons 100 to 250

Platoon (Troop) 2 or more Squads 16 to 50 1st Lt.

Squad 2 or more Sections 8 to 24 Sgt.

Section 4 to 12 Sgt.

http://www.hierarchystructure.com/british-military-hierarchy/

Unit Name Consists of [1]: Approx Number of men:

Brigade 3 or more Battalions 1500 to 3500

Regiment[2] 2 or more Battalions 1000 to 2000

Battalion 4 or more Companies 400 to 1000

Company 2 or more Platoons 100 to 250

Platoon (Troop) 2 or more Squads 16 to 50 1st Lt.

Squad 2 or more Sections 8 to 24 Sgt.

Section 4 to 12 Sgt.

http://www.hierarchystructure.com/british-military-hierarchy/

ATS-Army | WAAF-RAF | WRNS-RN |

Auxiliary vs Military Ranks WW2

https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/originals/58/cb/75/58cb75624452c757cbc659f636928d31.jpg

http://www.hierarchystructure.com/british-military-hierarchy/

Tuesday, June 26, 2018

Camp X - STS 103

.

16-2-18 Inside Camp X: Trained to Forget | X Company | CBC > .24-4-20 Canadian Defense Spending is a Joke | Solutions? - Waro > .

15-6-24 Camp X - U.S. Spy Training School = Americans Unaware - Smith > .

16-6-24 Inside Camp X: Hand-to-Hand Combat | CBC > .

Camp X was the unofficial name of the secret Special Training School No. 103, a WW2 British paramilitary installation for training covert agents in the methods required for success in clandestine operations. It was located on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario between Whitby and Oshawa in Ontario, Canada. The area is known today as Intrepid Park, after the code name for Sir William Stephenson, Director of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), who established the program to create the training facility.

The facility was jointly operated by the Canadian military, with help from Foreign Affairs and the RCMP but commanded by the BSC; it also had close ties with MI-6. In addition to the training program, the Camp had a communications tower that could send and transmit radio and telegraph communications, called Hydra.

Camp X was established December 6, 1941 by the chief of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), Sir William Stephenson, a Canadian from Winnipeg, Manitoba and a close confidant of Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The camp was originally designed to link Britain and the US at a time when the US was forbidden by the Neutrality Act to be directly involved in WW2.

On the day before the attack on Pearl Harbor and America's entry into the war, Camp X had opened for the purpose of training Allied agents from the Special Operations Executive (SOE), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) intended to be dropped behind enemy lines for clandestine missions as saboteurs and spies.

However, even before the United States entered the war on December 8, 1941, agents from America's intelligence services expressed an interest in sending personnel for training at the soon to be opened Camp X. Agents from the FBI and the OSS (forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, or CIA) secretly attended Camp X in early 1942; at least a dozen attended at least some training.

"Trainees at the camp learned sabotage techniques, subversion, intelligence gathering, lock picking, explosives training, radio communications, encode/decode, recruiting techniques for partisans, the art of silent killing and unarmed combat."

The facility was jointly operated by the Canadian military, with help from Foreign Affairs and the RCMP but commanded by the BSC; it also had close ties with MI-6. In addition to the training program, the Camp had a communications tower that could send and transmit radio and telegraph communications, called Hydra.

Camp X was established December 6, 1941 by the chief of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), Sir William Stephenson, a Canadian from Winnipeg, Manitoba and a close confidant of Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The camp was originally designed to link Britain and the US at a time when the US was forbidden by the Neutrality Act to be directly involved in WW2.

On the day before the attack on Pearl Harbor and America's entry into the war, Camp X had opened for the purpose of training Allied agents from the Special Operations Executive (SOE), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) intended to be dropped behind enemy lines for clandestine missions as saboteurs and spies.

However, even before the United States entered the war on December 8, 1941, agents from America's intelligence services expressed an interest in sending personnel for training at the soon to be opened Camp X. Agents from the FBI and the OSS (forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, or CIA) secretly attended Camp X in early 1942; at least a dozen attended at least some training.

After Stephenson established the facility and acted as the Camp's first head, the first commandant was Lt. Col. Arthur Terence Roper-Caldbeck. The most notable individual in the Camp's history was Colonel William "Wild Bill" Donovan, war-time head of the OSS, who credited Stephenson with teaching Americans about foreign intelligence gathering. The CIA even named their recruit training facility "The Farm", a nod to the original farm that existed at the Camp X site.

Camp X was jointly operated by the BSC and the Government of Canada. There were several names for the school: S 25-1-1 by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Project-J by the Canadian military, and Special Training School No. 103. The latter was set by the Special Operations Executive, administered under the cover of the Ministry of Economic Warfare (MEW) which operated the facility. In 1942 the Commandant of the camp was Lieutenant R. M. Brooker of the British Army.

In addition to operating an excellent document forging facility, Camp X trained numerous Allied covert operatives. An estimate published by the CBC states that "By war's end, between 500 and 2,000 Allied agents had been trained (figures vary) and sent abroad..." behind enemy lines.

Reports indicate that graduates worked as "secret agents, security personnel, intelligence officers, or psychological warfare experts, serving in clandestine operations". Many were captured, tortured, and executed; survivors received no individual recognition for their efforts."

The predominant close-combat trainer for the British Special Operations Executive was William E. Fairbairn, called "Dangerous Dan". With instructor Eric A. Sykes, they trained numerous agents for the SOE and OSS. Fairbairn's technique was "Get down in the gutter, and win at all costs … no more playing fair … to kill or be killed."

Camp X was jointly operated by the BSC and the Government of Canada. There were several names for the school: S 25-1-1 by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Project-J by the Canadian military, and Special Training School No. 103. The latter was set by the Special Operations Executive, administered under the cover of the Ministry of Economic Warfare (MEW) which operated the facility. In 1942 the Commandant of the camp was Lieutenant R. M. Brooker of the British Army.

In addition to operating an excellent document forging facility, Camp X trained numerous Allied covert operatives. An estimate published by the CBC states that "By war's end, between 500 and 2,000 Allied agents had been trained (figures vary) and sent abroad..." behind enemy lines.

Reports indicate that graduates worked as "secret agents, security personnel, intelligence officers, or psychological warfare experts, serving in clandestine operations". Many were captured, tortured, and executed; survivors received no individual recognition for their efforts."

The predominant close-combat trainer for the British Special Operations Executive was William E. Fairbairn, called "Dangerous Dan". With instructor Eric A. Sykes, they trained numerous agents for the SOE and OSS. Fairbairn's technique was "Get down in the gutter, and win at all costs … no more playing fair … to kill or be killed."

"Trainees at the camp learned sabotage techniques, subversion, intelligence gathering, lock picking, explosives training, radio communications, encode/decode, recruiting techniques for partisans, the art of silent killing and unarmed combat."

One of the unique features of Camp X was Hydra, a highly sophisticated telecommunications relay station established in May 1942 by engineer Benjamin deForest Bayly. Bayly was the assistant director, with British army rank of lieutenant colonel. He also invented a very fast offline, one-time tape cipher machine for coding/decoding telegraph transmissions labelled the Rockex or "Telekrypton".

Communication training, including Morse code, was also provided. The camp was so secret that even Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was unaware of its full purpose.

Traitors ..

After it had closed, starting in the autumn of 1945, Camp X was used by the RCMP as a secure location for interviewing Soviet embassy GRU cypher-clerk Igor Gouzenko, who had defected to Canada on September 5, 1945 (3 days after end of WW2) and revealed an extensive Soviet espionage operation in the country. Gouzenko provided 109 documents on the USSR′s espionage activities in the West. This forced Canada′s Prime Minister Mackenzie King to call a Royal Commission to investigate espionage in Canada.

Gouzenko exposed Soviet intelligence' efforts to steal nuclear secrets as well as the technique of planting sleeper agents. The "Gouzenko Affair" is often credited as a triggering event of the Cold War, with historian Jack Granatstein stating it was "the beginning of the Cold War for public opinion" and journalist Robert Fulford writing he was "absolutely certain the Cold War began in Ottawa". Granville Hicks described Gouzenko's actions as having "awakened the people of North America to the magnitude and the danger of Soviet espionage".

Gouzenko passed along copies of GRU documents implicating British physicist Nunn May, including details of the proposed meeting in London.

Nunn May did not go to the British Museum meeting, but he was arrested in March 1946. Nunn May confessed to espionage. On 1 May 1946, he was sentenced to ten years' hard labour. He was released in late 1952, after serving six and a half years.

Gouzenko and his family spent two years at the Camp X facility.

Traitors ..

After it had closed, starting in the autumn of 1945, Camp X was used by the RCMP as a secure location for interviewing Soviet embassy GRU cypher-clerk Igor Gouzenko, who had defected to Canada on September 5, 1945 (3 days after end of WW2) and revealed an extensive Soviet espionage operation in the country. Gouzenko provided 109 documents on the USSR′s espionage activities in the West. This forced Canada′s Prime Minister Mackenzie King to call a Royal Commission to investigate espionage in Canada.

Gouzenko exposed Soviet intelligence' efforts to steal nuclear secrets as well as the technique of planting sleeper agents. The "Gouzenko Affair" is often credited as a triggering event of the Cold War, with historian Jack Granatstein stating it was "the beginning of the Cold War for public opinion" and journalist Robert Fulford writing he was "absolutely certain the Cold War began in Ottawa". Granville Hicks described Gouzenko's actions as having "awakened the people of North America to the magnitude and the danger of Soviet espionage".

Gouzenko passed along copies of GRU documents implicating British physicist Nunn May, including details of the proposed meeting in London.

Nunn May did not go to the British Museum meeting, but he was arrested in March 1946. Nunn May confessed to espionage. On 1 May 1946, he was sentenced to ten years' hard labour. He was released in late 1952, after serving six and a half years.

Gouzenko and his family spent two years at the Camp X facility.

The training facility closed before the end of 1944; the buildings were removed in 1969 and a monument was erected at the site.

Monday, May 21, 2018

Helmets - WW1, WW2

2020 - Is This The World's Most Advanced Pilot Helmet? - Spark > .

The Brodie helmet, widely used during the first World War, had some serious design flaws. But thanks to those flaws we now have a staggeringly accurate map of the brain.

At the outbreak of WW1, none of the combatants were issued with any form of protection for the head other than cloth, felt, or leather headgear, designed at most to protect against saber cuts, that offered no protection from modern weapons.

Brodie's design resembled the medieval infantry kettle hat or chapel-de-fer, unlike the German Stahlhelm, which resembled the medieval sallet. The Brodie had a shallow circular crown with a wide brim around the edge, a leather liner and a leather chinstrap. The helmet's "soup bowl" shape was designed to protect the wearer's head and shoulders from shrapnel shell projectiles bursting from above the trenches. The design allowed the use of relatively thick steel that could be formed in a single pressing while maintaining the helmet's thickness. This made it more resistant to projectiles but it offered less protection to the lower head and neck than other helmets.

The original design (Type A) was made of mild steel with a brim 1.5–2 inches (38–51 mm) wide. The Type A was in production for just a few weeks before the specification was changed and the Type B was introduced in October 1915. The specification was altered at the suggestion of Sir Robert Hadfield to a harder steel with 12% manganese content, which became known as "Hadfield steel", which was virtually impervious to shrapnel hitting from above. Ballistically this increased protection for the wearer by 10 per cent. It could withstand a .45 caliber pistol bullet traveling at 600 feet (180 m) per second fired at a distance of 10 feet (3.0 m). It also had a narrower brim and a more domed crown.

Stahlhelm (plural Stahlhelme) is German for "steel helmet". The Imperial German Army began to replace the traditional boiled leather Pickelhaube (spiked combat helmet) with the Stahlhelm during World War I in 1916. The term Stahlhelm refers both to a generic steel helmet, and more specifically to the distinctive (and iconic) German design.

The Stahlhelm, with its distinctive "coal scuttle" shape, was instantly recognizable and became a common element of military propaganda on both sides, just like the Pickelhaube before it.

In early 1915, Dr. Friedrich Schwerd of the Technical Institute of Hanover had carried out a study of head wounds suffered during trench warfare and submitted a recommendation for steel helmets, shortly after which he was ordered to Berlin. Schwerd then undertook the task of designing and producing a suitable helmet, broadly based on the 15th-century sallet, which provided good protection for the head and neck.

After lengthy development work, which included testing a selection of German and Allied headgear, the first Stahlhelme were tested in November 1915 at the Kummersdorf Proving Ground and then field tested by the 1st Assault Battalion. Thirty thousand examples were ordered, but it was not approved for general issue until New Year of 1916, hence it is most usually referred to as the "Model 1916". In February 1916 it was distributed to troops at Verdun, following which the incidence of serious head injuries fell dramatically. The first German troops to use this helmet were the stormtroopers of the Sturm-Bataillon Nr. 5 (Rohr), which was commanded by captain Willy Rohr.

In contrast to the Hadfield steel used in the British Brodie helmet, the Germans used a harder martensitic silicon/nickel steel. As a result, and also due to the helmet's form, the Stahlhelm had to be formed in heated dies at a greater unit cost than the British helmet, which could be formed in one piece.

At the outbreak of WW1, none of the combatants were issued with any form of protection for the head other than cloth, felt, or leather headgear, designed at most to protect against saber cuts, that offered no protection from modern weapons.

When trench warfare began, the number of casualties on all sides suffering from severe head wounds (more often caused by shrapnel bullets or shell fragments than by gunfire) increased dramatically, since the head was typically the most exposed part of the body when in a trench.

The huge number of lethal head wounds that modern artillery weapons inflicted upon the French Army led them to introduce the first modern steel helmets in the summer of 1915. The first French helmets were bowl-shaped steel "skullcaps" worn under the cloth caps. These rudimentary helmets were soon replaced by the Model 1915 Adrian helmet (Casque Adrian), designed by August-Louis Adrian. The idea was later adopted by most other combatant nations.

The British and Commonwealth troops followed with the Brodie helmet (a development of which was also later worn by US forces) and the Germans with the Stahlhelm.

The Brodie helmet is a steel combat helmet designed and patented in London in 1915 by John Leopold Brodie. The term Brodie is often misused. It is correctly applied only to the original 1915 Brodie's Steel Helmet, War Office Pattern. A modified form of it became the Helmet, steel, Mark I in Britain and the M1917 Helmet in the U.S. Colloquially, it was called the shrapnel helmet, battle bowler, Tommy helmet, tin hat, and in the United States the doughboy helmet. It was also known as the dishpan hat, tin pan hat, washbasin, battle bowler (when worn by officers), and Kelly helmet. The German Army called it the Salatschüssel (salad bowl).

The original design (Type A) was made of mild steel with a brim 1.5–2 inches (38–51 mm) wide. The Type A was in production for just a few weeks before the specification was changed and the Type B was introduced in October 1915. The specification was altered at the suggestion of Sir Robert Hadfield to a harder steel with 12% manganese content, which became known as "Hadfield steel", which was virtually impervious to shrapnel hitting from above. Ballistically this increased protection for the wearer by 10 per cent. It could withstand a .45 caliber pistol bullet traveling at 600 feet (180 m) per second fired at a distance of 10 feet (3.0 m). It also had a narrower brim and a more domed crown.

As the German army behaved hesitantly in the development of an effective head protection, some units developed provisional helmets in 1915. Stationed in the rocky area of the Vosges the Army Detachment "Gaede" recorded significantly more head injuries caused by stone and shell splinters than did troops in other sectors of the front. The artillery workshop of the Army Detachment developed a helmet that consisted of a leather cap with a steel plate (6 mm thickness). The plate protected not only the forehead but also the eyes and nose.

The Stahlhelm, with its distinctive "coal scuttle" shape, was instantly recognizable and became a common element of military propaganda on both sides, just like the Pickelhaube before it.

After lengthy development work, which included testing a selection of German and Allied headgear, the first Stahlhelme were tested in November 1915 at the Kummersdorf Proving Ground and then field tested by the 1st Assault Battalion. Thirty thousand examples were ordered, but it was not approved for general issue until New Year of 1916, hence it is most usually referred to as the "Model 1916". In February 1916 it was distributed to troops at Verdun, following which the incidence of serious head injuries fell dramatically. The first German troops to use this helmet were the stormtroopers of the Sturm-Bataillon Nr. 5 (Rohr), which was commanded by captain Willy Rohr.

In contrast to the Hadfield steel used in the British Brodie helmet, the Germans used a harder martensitic silicon/nickel steel. As a result, and also due to the helmet's form, the Stahlhelm had to be formed in heated dies at a greater unit cost than the British helmet, which could be formed in one piece.

From 1936, the Mark I Brodie helmet was fitted with an improved liner and an elasticated (actually, sprung) webbing chin strap. This final variant served until late 1940, when it was superseded by the slightly modified Mk II, which served the British and Commonwealth forces throughout World War II. British paratroopers and airborne forces used the Helmet Steel Airborne Troop.

Several Commonwealth nations, such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa, produced local versions of the MK II, which can be distinguished from those made in Britain.

During this period, the helmet was also used by the police, the fire brigade and ARP wardens in Britain. The helmets for the ARP wardens came in two principal variants, black with a white "W" for wardens and white with a black "W" for senior ranks (additional black stripes denoted seniority within the warden service); however numerous different patterns were used. A civilian pattern was also available for private purchase, known as the Zuckerman helmet, which was a little deeper but made from ordinary mild steel.

Several Commonwealth nations, such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa, produced local versions of the MK II, which can be distinguished from those made in Britain.

During this period, the helmet was also used by the police, the fire brigade and ARP wardens in Britain. The helmets for the ARP wardens came in two principal variants, black with a white "W" for wardens and white with a black "W" for senior ranks (additional black stripes denoted seniority within the warden service); however numerous different patterns were used. A civilian pattern was also available for private purchase, known as the Zuckerman helmet, which was a little deeper but made from ordinary mild steel.

Tuesday, February 13, 2018

42-8-19 Dieppe Raid

The Raid on Dieppe: Dieppe, France, 19 August 1942 .

"The Dieppe Raid, also known as the Battle of Dieppe, Operation Rutter during planning stages, and by its final official code-name Operation Jubilee, was an Allied attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe during the Second World War. The raid took place on the northern coast of France on 19 August 1942. The assault began at 5:00 a.m., and by 10:50 a.m. the Allied commanders were forced to call a retreat. Over 6,000 infantrymen, predominantly Canadian, were supported by The Calgary Regiment of the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade and a strong force of Royal Navy and smaller Royal Air Force landing contingents. It involved 5,000 Canadians, 1,000 British troops, and 50 United States Army Rangers.

Objectives included seizing and holding a major port for a short period, both to prove that it was possible and to gather intelligence. Upon retreat, the Allies also wanted to destroy coastal defences, port structures and all strategic buildings. The raid had the added objectives of boosting morale and demonstrating the firm commitment of the United Kingdom to open a western front in Europe.

Virtually none of these objectives were met. Allied fire support was grossly inadequate and the raiding force was largely trapped on the beach by obstacles and German fire. Less than 10 hours after the first landings, the last Allied troops had all been either killed, evacuated, or left behind to be captured by the Germans. Instead of a demonstration of resolve, the bloody fiasco showed the world that the Allies could not hope to invade France for a long time. Some intelligence successes were achieved, including electronic intelligence.

Of the 6,086 men who made it ashore, 3,623 (almost 60%) were either killed, wounded or captured. The Royal Air Force failed to lure the Luftwaffe into open battle, and lost 106 aircraft (at least 32 to anti-aircraft fire or accidents), compared to 48 lost by the Luftwaffe. The Royal Navy lost 33 landing craft and one destroyer. The events at Dieppe influenced preparations for the North African (Operation Torch) and Normandy landings (Operation Overlord)."

GC+ blunders.

"From conception to execution, the Dieppe raid was filled with unclear objectives and poor planning. Why did the Allies undertake such an ill-fated attack on this German-occupied French city? Find out here, along with a detailed account of what went wrong—from bad timing to overambitious strategies to unexpectedly difficult terrain."

Dieppe 1942 - Slaughter on the Shingle - MaFe > .

*World War Two heroine 'Angel of Dieppe' *

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-43844090

42-8-19 Dieppe Raid

The Dieppe Raid, also known as the Battle of Dieppe, Operation Rutter during planning stages, and by its final official code-name Operation Jubilee, was an Allied attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe during the Second World War. The raid took place on the northern coast of France on 19 August 1942. The assault began at 5:00 a.m., and by 10:50 a.m. the Allied commanders were forced to call a retreat. Over 6,000 infantrymen, predominantly Canadian, were supported by The Calgary Regiment of the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade and a strong force of Royal Navy and smaller Royal Air Force landing contingents. It involved 5,000 Canadians, 1,000 British troops, and 50 United States Army Rangers.

Objectives included seizing and holding a major port for a short period, both to prove that it was possible and to gather intelligence. Upon retreat, the Allies also wanted to destroy coastal defences, port structures and all strategic buildings. The raid had the added objectives of boosting morale and demonstrating the firm commitment of the United Kingdom to open a western front in Europe.

Virtually none of these objectives were met. Allied fire support was grossly inadequate and the raiding force was largely trapped on the beach by obstacles and German fire. Less than 10 hours after the first landings, the last Allied troops had all been either killed, evacuated, or left behind to be captured by the Germans. Instead of a demonstration of resolve, the bloody fiasco showed the world that the Allies could not hope to invade France for a long time. Some intelligence successes were achieved, including electronic intelligence.

Of the 6,086 men who made it ashore, 3,623 (almost 60%) were either killed, wounded or captured. The Royal Air Force failed to lure the Luftwaffe into open battle, and lost 106 aircraft (at least 32 to anti-aircraft fire or accidents), compared to 48 lost by the Luftwaffe. The Royal Navy lost 33 landing craft and one destroyer. The events at Dieppe influenced preparations for the North African (Operation Torch) and Normandy landings (Operation Overlord).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dieppe_Raid

"From conception to execution, the Dieppe raid was filled with unclear objectives and poor planning. Why did the Allies undertake such an ill-fated attack on this German-occupied French city? Find out here, along with a detailed account of what went wrong—from bad timing to overambitious strategies to unexpectedly difficult terrain."

Dieppe Raid: Catastrophe on the Beach—1942 | The Great Courses Plus

Friday, October 13, 2017

Princess Elizabeth's Broadcast - 40-10-13

Princess Elizabeth's First Broadcast - October 13, 1940 > .

Princess Elizabeth Broadcasts To The Nation on Children's Hour (1940) > .

Princess Elizabeth Broadcasts (1940) > .

Queen Elizabeth II's First Speech was Churchill's idea > .Princess Elizabeth Broadcasts To The Nation on Children's Hour (1940) > .

Princess Elizabeth Broadcasts (1940) > .

https://www.royal.uk/wartime-broadcast-1940 .

Almost 80 years later ...

1920-4-5 Coronavirus: The Queen gives special address during pandemic > .

Almost 80 years later ...

1920-4-5 Coronavirus: The Queen gives special address during pandemic > .

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Thursday, March 16, 2017

44-7-1 Bretton Woods Conference 44-7-21

2019 (Bretton Woods, Gold Standard) New World Order - Caspian > .1931-9-21 Britain abandoned gold standard; Parliament's Amendment Act - HiPo > .

Currencies - Way of the Triffin - Weighs 'n Means >> .

The Nixon shock was a series of economic measures undertaken by United States President Richard Nixon in 1971, in response to increasing inflation, the most significant of which were wage and price freezes, surcharges on imports, and the unilateral cancellation of the direct international convertibility of the United States dollar to gold.

While Nixon's actions did not formally abolish the existing Bretton Woods system of international financial exchange, the suspension of one of its key components effectively rendered the Bretton Woods system inoperative. While Nixon publicly stated his intention to resume direct convertibility of the dollar after reforms to the Bretton Woods system had been implemented, all attempts at reform proved unsuccessful. By 1973, the Bretton Woods system was replaced de facto by the current regime based on freely floating fiat currencies.

Currency Manipulation - Weighs 'n Means >> .

Printing Money - Central Banks, Fed - Weighs 'n Means >> .

War, Money, Civilization - Weighs 'n Means >> .

Printing Money - Central Banks, Fed - Weighs 'n Means >> .

War, Money, Civilization - Weighs 'n Means >> .

>> Weighs 'n Means >>

Inflation ..

Monetarism ..

Early in the Second World War, John Maynard Keynes of the British Treasury and Harry Dexter White of the United States Treasury Department independently began to develop ideas about the financial order of the postwar world. After negotiation between officials of the United States and United Kingdom, and consultation with some other Allies, a "Joint Statement by Experts on the Establishment of an International Monetary Fund," was published simultaneously in a number of Allied countries on April 21, 1944. On May 25, 1944, the U.S. government invited the Allied countries to send representatives to an international monetary conference, "for the purpose of formulating definite proposals for an International Monetary Fund and possibly a Bank for Reconstruction and Development." (The word "International" was only added to the Bank's title late in the Bretton Woods Conference.) The United States also invited a smaller group of countries to send experts to a preliminary conference in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to develop draft proposals for the Bretton Woods conference. The Atlantic City conference was held from June 15–30, 1944.

Preparing to rebuild the international economic system while World War II was still raging, 730 delegates from all 44 Allied nations gathered at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, for the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, also known as the Bretton Woods Conference. The delegates deliberated during 1–22 July 1944, and signed the Bretton Woods agreement on its final day. Setting up a system of rules, institutions, and procedures to regulate the international monetary system, these accords established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which today is part of the World Bank Group. The United States, which controlled two thirds of the world's gold, insisted that the Bretton Woods system rest on both gold and the US dollar. Soviet representatives attended the conference but later declined to ratify the final agreements, charging that the institutions they had created were "branches of Wall Street". These organizations became operational in 1945 after a sufficient number of countries had ratified the agreement.

The Bretton Woods Conference had three main results: (1) Articles of Agreement to create the IMF, whose purpose was to promote stability of exchange rates and financial flows. (2) Articles of Agreement to create the IBRD, whose purpose was to speed reconstruction after the Second World War and to foster economic development, especially through lending to build infrastructure. (3) Other recommendations for international economic cooperation. The Final Act of the conference incorporated these agreements and recommendations.

Within the Final Act, the most important part in the eyes of the conference participants and for the later operation of the world economy was the IMF agreement. Its major features were:

Within the Final Act, the most important part in the eyes of the conference participants and for the later operation of the world economy was the IMF agreement. Its major features were:

- An adjustably pegged foreign exchange market rate system: Exchange rates were pegged to gold. Governments were only supposed to alter exchange rates to correct a "fundamental disequilibrium."

- Member countries pledged to make their currencies convertible for trade-related and other current account transactions. There were, however, transitional provisions that allowed for indefinite delay in accepting that obligation, and the IMF agreement explicitly allowed member countries to regulate capital flows. The goal of widespread current account convertibility did not become operative until December 1958, when the currencies of the IMF's Western European members and their colonies became convertible.

- As it was possible that exchange rates thus established might not be favourable to a country's balance of payments position, governments had the power to revise them by up to 10% from the initially agreed level ("par value") without objection by the IMF. The IMF could concur in or object to changes beyond that level. The IMF could not force a member to undo a change, but could deny the member access to the resources of the IMF.

- All member countries were required to subscribe to the IMF's capital. Membership in the IBRD was conditioned on being a member of the IMF. Voting in both institutions was apportioned according to formulas giving greater weight to countries contributing more capital ("quotas").

The Bretton Woods system of monetary management established the rules for commercial and financial relations among the United States, Canada, Western European countries, Australia, and Japan after the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement. The Bretton Woods system was the first example of a fully negotiated monetary order intended to govern monetary relations among independent states. The chief features of the Bretton Woods system were an obligation for each country to adopt a monetary policy that maintained its external exchange rates within 1 percent by tying its currency to gold and the ability of the IMF to bridge temporary imbalances of payments. Also, there was a need to address the lack of cooperation among other countries and to prevent competitive devaluation of the currencies as well.

On 15 August 1971, the United States unilaterally terminated convertibility of the US dollar to gold, effectively bringing the Bretton Woods system to an end and rendering the dollar a fiat currency. This action, referred to as the Nixon shock, created the situation in which the U.S. dollar became a reserve currency used by many states. At the same time, many fixed currencies(such as the pound sterling) also became free-floating.

On 15 August 1971, the United States unilaterally terminated convertibility of the US dollar to gold, effectively bringing the Bretton Woods system to an end and rendering the dollar a fiat currency. This action, referred to as the Nixon shock, created the situation in which the U.S. dollar became a reserve currency used by many states. At the same time, many fixed currencies(such as the pound sterling) also became free-floating.

While Nixon's actions did not formally abolish the existing Bretton Woods system of international financial exchange, the suspension of one of its key components effectively rendered the Bretton Woods system inoperative. While Nixon publicly stated his intention to resume direct convertibility of the dollar after reforms to the Bretton Woods system had been implemented, all attempts at reform proved unsuccessful. By 1973, the Bretton Woods system was replaced de facto by the current regime based on freely floating fiat currencies.

Thursday, January 5, 2017

Saturday, December 31, 2016

● Interbellum >> series

Appeasement, Isolationism vs Autocrats - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - economics, society - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - technology - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - economics, society - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - technology - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - treaties - RaWa >> .

Women - WW1, interbellum - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - Asia - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - Eastern Europe, USSR - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - Italy, Mediterranean - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - Germany - RaWa >> .

Women - WW1, interbellum - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - Asia - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - Eastern Europe, USSR - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - Italy, Mediterranean - RaWa >> .

Interbellum - Germany - RaWa >> .

Tuesday, December 13, 2016

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

● British Empire - Fall

1848 European Tensions, WW1, Versailles 1919 ..

Australian States, Territories - 1900+ ..

Australian States, Territories - 1900+ ..

Enoch Powell's Warning ..UK Rise & Fall ..

Unemployment in Britain, 1959 ..

Western Colonialism and Decolonisation ..

56-10-29 Suez Crisis 57-4-10 ..

Unemployment in Britain, 1959 ..

Western Colonialism and Decolonisation ..

56-10-29 Suez Crisis 57-4-10 ..

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

sī vīs pācem, parā bellum

igitur quī dēsīderat pācem praeparet bellum therefore, he who desires peace, let him prepare for war sī vīs pācem, parā bellum if you wan...

-

>>> Economic > >>> Geopolitics > >>> Military > >>> Resources > > >> Sociopoli...

-

2026 >> America DUH Rogue >> > Assailed (by DUH), Corrupted (UN, UNWRA, ICC) - Present Tense >> . Democracy ⟺ Autho...

-

>> Iran, XIR >> > Iran - Tam O >> . Iran - Strikes, Crises, Protests, Intervention? - Bellum Praeparet >> . Ira...