Sunday, February 10, 2019

Sealion

.

Sealion - Hitler Unable To Invade Britain | War Stories > .Operation Sea Lion: Hitler's Daring Plan to Invade Britain... | WarsofTheWorld > .

Goering's False Promise: Why Operation Sea Lion Failed | War Stories > .

? Sealion ?

[Life under a Nazi occupier] is, to be sure, a question that can never be definitively answered and, since Britons can never know how they would have acted under the heel of Nazi oppression, they are likely to continue speculating about it. Perhaps that is the one characteristic that truly does separate Britons from other Europeans.

https://aeon.co/essays/the-many-counterfactual-histories-of-nazi-britain .

https://history.blog.gov.uk/category/second-world-war/

Timewatch - Operation Sealion (BBC 1998)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ux-J8B8fURk

Great Blunders of WWII: Operation Sea Lion (The Mission That Never Was) 10

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ya4Xod9Qq3o

What if Operation Sea Lion actually Happened? - mapping

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NWKJwi1QNw8

What if? Hitlers Britain 1of2 The Nazi Occupation of Britain

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rJFmRBoG0Ms

What if? When hitler invaded Britain- Non Academic docudrama from 2004

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7NnsRCt8TGM

What if? Hitlers Britain 2of2 The Secret of the British Resistance

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ECi-1JXq2Yc

Hitler's Britain - Alternate History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jXESMPPK7rc

What if? Alternative History - Operation Sealion

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jXESMPPK7rc

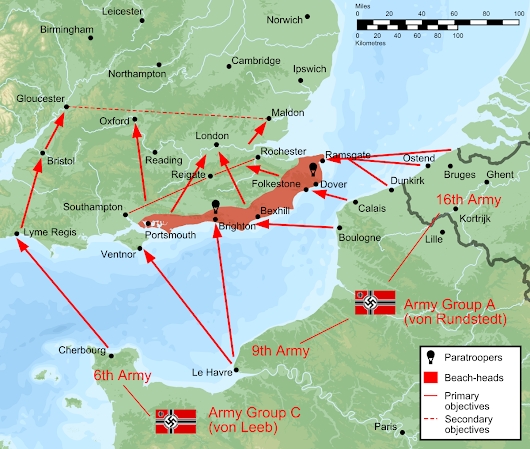

German battle plan - Operation Sea Lion map

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Sea_Lion#/media/File:OperationSealion.svg

40-8-17 Naval Blockade of British Isles ..

Planning for Invasion

For a 12-month period after May 1940 the threat of invasion exercised those in power. Their discussions emphasised the need for decisive leadership and clear instruction. However they also showed just how difficult these were to achieve when facing a threat which had previously been inconceivable.

The threat of invasion had been discussed in government since October 1939. It was not until spring 1940, however, that it was treated as a serious possibility. The disastrous Norwegian campaign of April 1940 focused attention. And the Nazis’ rapid advance into Western Europe after 10 May pushed the matter to the very top of the government’s agenda. It was for this reason that the ‘Invasion of Great Britain’ was discussed on 19 occasions during the first three weeks of Winston Churchill’s premiership.

Invasion Publicity during the Second World War .

https://aeon.co/essays/the-many-counterfactual-histories-of-nazi-britain .

Timewatch - Operation Sealion (BBC 1998)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ux-J8B8fURk

Great Blunders of WWII: Operation Sea Lion (The Mission That Never Was) 10

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ya4Xod9Qq3o

What if Operation Sea Lion actually Happened? - mapping

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NWKJwi1QNw8

What if? Hitlers Britain 1of2 The Nazi Occupation of Britain

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rJFmRBoG0Ms

What if? When hitler invaded Britain- Non Academic docudrama from 2004

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7NnsRCt8TGM

What if? Hitlers Britain 2of2 The Secret of the British Resistance

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ECi-1JXq2Yc

Hitler's Britain - Alternate History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jXESMPPK7rc

What if? Alternative History - Operation Sealion

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jXESMPPK7rc

German battle plan - Operation Sea Lion map

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Sea_Lion#/media/File:OperationSealion.svg

40-8-17 Naval Blockade of British Isles ..

Planning for Invasion

For a 12-month period after May 1940 the threat of invasion exercised those in power. Their discussions emphasised the need for decisive leadership and clear instruction. However they also showed just how difficult these were to achieve when facing a threat which had previously been inconceivable.

The threat of invasion had been discussed in government since October 1939. It was not until spring 1940, however, that it was treated as a serious possibility. The disastrous Norwegian campaign of April 1940 focused attention. And the Nazis’ rapid advance into Western Europe after 10 May pushed the matter to the very top of the government’s agenda. It was for this reason that the ‘Invasion of Great Britain’ was discussed on 19 occasions during the first three weeks of Winston Churchill’s premiership.

The withdrawal from Dunkirk served to underline the perilous situation that Britain faced. Although the evacuation of troops was a success, large amounts of equipment had been lost and military leaders feared that Hitler would seek to exploit the confusion caused. Plans were hastily drawn up to meet the imminent threat of invasion. A Home Defence Executive was established, men were encouraged to join the recently-formed Local Defence Volunteers (better-known as the Home Guard), road signs were removed, and large parts of the South East were designated as Defence Areas.

One of the greatest difficulties facing the government was the need to explain the situation to the public. This was the responsibility of the Ministry of Information’s ‘Emergency Planning Committee’. Formed on 22 May 1940, five days before the first troops left northern France, it called for swift action to counter public apprehension. The War Cabinet agreed, and invited the Ministry to prepare a publicity campaign. It was asked to include a series of instructions explaining the steps that should be taken in the event of an invasion.

The Ministry of Information did not attempt to do this alone. Instead it worked with the Home Defence Executive of the War Office and the Home Office-led Ministry of Home Security in an effort to ensure a consistent message across government. The main outcome of their discussions was a leaflet with the unimaginative title ‘If the Germans Invade Great Britain’. It included a mixture of practical instructions and generic advice. It was stressed, for instance, that ‘In the event of an invasion … you must remain where you are. The order is “STAY PUT”’. This was the first of seven ‘rules’ which also included warnings against rumour, the need to keep watch, and advice for constructing road blocks.

The collaboration between the Home Security, Home Defence and the Ministry of Information was not without its difficulties. The civil authorities’ main aim was to stop ‘responsible people’ from ‘running away’ unnecessarily and were unwilling to countenance any form of civilian resistance. The military wanted to ensure that Defence Areas were kept clear for troops and privately hoped ‘inessential’ civilians would be evacuated. The Ministry of Information, by contrast, wanted to ‘rouse the public’ by including an instruction for anyone behind enemy lines to: ‘Do everything in your power to render [the German troops’] position difficult. Be clever. Be brave’. Such were the differences in approach that the original draft was deemed ‘entirely unsuitable for publication’ by its primary author!

These differences spilled over into the War Cabinet. Ministers were well-aware that their French counterparts had been unable to stop a flood of refugees from leaving Paris, and that this had made it more difficult for French forces to operate during the battle of France. Yet it was feared that the appearance of support for active resistance would encourage reprisals and could not be justified under international law. Thus while it was thought that advice about road blocks and the defence of factories could be retained in a shortened form, the instruction to ‘harass the enemy’ was deemed ‘unsuitable for incorporation in a document of this character’. It was replaced with the less evocative clause: ‘Think before you act. But think always of your country before you think of yourself’.

The revised text bore the hallmarks of compromise. Its tone oscillated between confident assertions that any invading force would be ‘driven out’ and dire warnings that ‘If you run away … you will be machine gunned from the air’. Many questions also remained unanswered. How, for example, did you make a car ‘useless to anyone except yourself’ when removing the ignition key was not enough? What did it mean for ‘Managers and workmen [to] organise some system by which a sudden attack can be resisted’? And when would ‘more detailed instructions’ arrive? None of these questions were answered before the leaflet was released under the title If the Invader Comeson 18 June 1940. Fifteen million copies of the leaflet – one for every household – were distributed during the next three days. This effort was supported by a publicity campaign. Poster-sized versions of the leaflet were sent to local authorities, Winston Churchill was persuaded to broadcast a version of his ‘Finest Hour’ speech on the BBC, the Minister of Information gave a press conference on the theme of ‘Fortress Britain’, and General Sir Hugh Elles (Commander in Chief of Civil Defence) broadcast a plea to ‘get the pamphlet into your system’. The press also got involved. For instance, the Daily Express urged readers to ‘Do what you are told’, while the Daily Mirrortook the uncompromising line that anyone found ‘refugee-ing about the roads … deserves to be shot’. Most other newspapers reprinted the seven rules in full.

The public’s reaction was more complicated. Anecdotal reports from the Ministry of Information’s Home Intelligence division suggested that the leaflet was generally well received. Despite being deemed a ‘little too wordy’ in Tunbridge Wells, it was described as ‘clearly written [and] easily understood’ in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and thought to be ‘a good idea’ by many in London. But an opinion poll undertaken using a representative sample found ‘evidence of the fact that the leaflet has not been taken seriously’. It estimated that 60% of the public had read the leaflet but that 20 %t had ‘not bothered’ as they saw ‘the threat of invasion as a joke’. A non-official report by Mass Observation was even more critical. It thought that the tone was ‘out of touch with common sense’ and treated the public as ‘blithering idiots’.

This mixed response did not come as a complete surprise. It had been recognised before publication that the instruction to ‘Stay Put’ was liable to be misunderstood, and it was less than a week before the Ministry of Information pushed for ‘more categorical orders, reasons and instructions’. Military sources conceded that many questions had been left unanswered and that the British public wanted to be told what was occurring. It was agreed that a second leaflet was needed to clarify that people should ‘[Stay put] unless given orders to the contrary’.

Officials within the Ministry of Information sought to use this opportunity to stress the publicity value of resistance. They argued that any order would fail unless it gave civilians ‘some prospect of being able to defend themselves’. However neither the Ministry of Home Security nor the Home Defence Executive were willing to amend their stances. The result was that all three departments again pursued their own approach, providing alternative drafts of a leaflet called Stay Where You Are for the War Cabinet. The former diplomat Harold Nicholson, who wrote one version, complained that it was ‘absurd to expect people to stay in their homes without telling them what to do’. His senior colleagues in the Ministry of Information eventually decided that their only option was to surrender responsibility for the leaflet to the Home Office.

Fifteen million copies of Stay Where You Are were distributed at the very end of July 1940 at a cost of £13,433. The focus remained on the need to ‘Stay Put’ but the tone was more active than before. So it was stressed that the public should ‘not attempt to join in the fight’ but noted that: ‘You have the right of every man and woman to do what you can to protect yourself, your family, and your home’. Such instructions was soon criticised for being ‘so indefinite as to be of little value’.

‘Beating the Invader’

Britain was not invaded in the summer of 1940. However this did not signal an end of the debate over how best to communicate the threat. Indeed the subject came back onto agenda in January 1941 as part of a thorough review of the government’s civil defence arrangements. The Ministry of Information were again asked to produce a leaflet which would ‘interpret and amplify’ If the Invader Comes and Stay Where You Are. The result was 15 short paragraphs that offered practical advice in a question-and-answer format. Car-owners were for the first time told to put their vehicles out of action by ‘Remov[ing the] distributer head and leads and empty[ing] the tank’.

The final leaflet was distributed in late April 1940 with the optimistic title Beating the Invader. Given what had come before, it is fitting that the delay was due to Winston Churchill’s dislike of the term ‘Stay Put’ and a disagreement with the War Office. It is similarly fitting that the leaflet was almost abandoned when concurrent attempts to ‘rouse the public’ through new posters and press advertisements was deemed to have failed. All of those involved believed that the government needed to show decisive leadership and offer clear instructions. Yet the experience of invasion publicity in the Second World War shows just how difficult it was to achieve these ends when facing a threat that many had hoped to avoid.

Further Reading

You can find out more about the history of the Ministry of Information at http://www.moidigital.ac.uk

One of the greatest difficulties facing the government was the need to explain the situation to the public. This was the responsibility of the Ministry of Information’s ‘Emergency Planning Committee’. Formed on 22 May 1940, five days before the first troops left northern France, it called for swift action to counter public apprehension. The War Cabinet agreed, and invited the Ministry to prepare a publicity campaign. It was asked to include a series of instructions explaining the steps that should be taken in the event of an invasion.

The Ministry of Information did not attempt to do this alone. Instead it worked with the Home Defence Executive of the War Office and the Home Office-led Ministry of Home Security in an effort to ensure a consistent message across government. The main outcome of their discussions was a leaflet with the unimaginative title ‘If the Germans Invade Great Britain’. It included a mixture of practical instructions and generic advice. It was stressed, for instance, that ‘In the event of an invasion … you must remain where you are. The order is “STAY PUT”’. This was the first of seven ‘rules’ which also included warnings against rumour, the need to keep watch, and advice for constructing road blocks.

The collaboration between the Home Security, Home Defence and the Ministry of Information was not without its difficulties. The civil authorities’ main aim was to stop ‘responsible people’ from ‘running away’ unnecessarily and were unwilling to countenance any form of civilian resistance. The military wanted to ensure that Defence Areas were kept clear for troops and privately hoped ‘inessential’ civilians would be evacuated. The Ministry of Information, by contrast, wanted to ‘rouse the public’ by including an instruction for anyone behind enemy lines to: ‘Do everything in your power to render [the German troops’] position difficult. Be clever. Be brave’. Such were the differences in approach that the original draft was deemed ‘entirely unsuitable for publication’ by its primary author!

These differences spilled over into the War Cabinet. Ministers were well-aware that their French counterparts had been unable to stop a flood of refugees from leaving Paris, and that this had made it more difficult for French forces to operate during the battle of France. Yet it was feared that the appearance of support for active resistance would encourage reprisals and could not be justified under international law. Thus while it was thought that advice about road blocks and the defence of factories could be retained in a shortened form, the instruction to ‘harass the enemy’ was deemed ‘unsuitable for incorporation in a document of this character’. It was replaced with the less evocative clause: ‘Think before you act. But think always of your country before you think of yourself’.

The revised text bore the hallmarks of compromise. Its tone oscillated between confident assertions that any invading force would be ‘driven out’ and dire warnings that ‘If you run away … you will be machine gunned from the air’. Many questions also remained unanswered. How, for example, did you make a car ‘useless to anyone except yourself’ when removing the ignition key was not enough? What did it mean for ‘Managers and workmen [to] organise some system by which a sudden attack can be resisted’? And when would ‘more detailed instructions’ arrive? None of these questions were answered before the leaflet was released under the title If the Invader Comeson 18 June 1940. Fifteen million copies of the leaflet – one for every household – were distributed during the next three days. This effort was supported by a publicity campaign. Poster-sized versions of the leaflet were sent to local authorities, Winston Churchill was persuaded to broadcast a version of his ‘Finest Hour’ speech on the BBC, the Minister of Information gave a press conference on the theme of ‘Fortress Britain’, and General Sir Hugh Elles (Commander in Chief of Civil Defence) broadcast a plea to ‘get the pamphlet into your system’. The press also got involved. For instance, the Daily Express urged readers to ‘Do what you are told’, while the Daily Mirrortook the uncompromising line that anyone found ‘refugee-ing about the roads … deserves to be shot’. Most other newspapers reprinted the seven rules in full.

The public’s reaction was more complicated. Anecdotal reports from the Ministry of Information’s Home Intelligence division suggested that the leaflet was generally well received. Despite being deemed a ‘little too wordy’ in Tunbridge Wells, it was described as ‘clearly written [and] easily understood’ in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and thought to be ‘a good idea’ by many in London. But an opinion poll undertaken using a representative sample found ‘evidence of the fact that the leaflet has not been taken seriously’. It estimated that 60% of the public had read the leaflet but that 20 %t had ‘not bothered’ as they saw ‘the threat of invasion as a joke’. A non-official report by Mass Observation was even more critical. It thought that the tone was ‘out of touch with common sense’ and treated the public as ‘blithering idiots’.

This mixed response did not come as a complete surprise. It had been recognised before publication that the instruction to ‘Stay Put’ was liable to be misunderstood, and it was less than a week before the Ministry of Information pushed for ‘more categorical orders, reasons and instructions’. Military sources conceded that many questions had been left unanswered and that the British public wanted to be told what was occurring. It was agreed that a second leaflet was needed to clarify that people should ‘[Stay put] unless given orders to the contrary’.

Officials within the Ministry of Information sought to use this opportunity to stress the publicity value of resistance. They argued that any order would fail unless it gave civilians ‘some prospect of being able to defend themselves’. However neither the Ministry of Home Security nor the Home Defence Executive were willing to amend their stances. The result was that all three departments again pursued their own approach, providing alternative drafts of a leaflet called Stay Where You Are for the War Cabinet. The former diplomat Harold Nicholson, who wrote one version, complained that it was ‘absurd to expect people to stay in their homes without telling them what to do’. His senior colleagues in the Ministry of Information eventually decided that their only option was to surrender responsibility for the leaflet to the Home Office.

Fifteen million copies of Stay Where You Are were distributed at the very end of July 1940 at a cost of £13,433. The focus remained on the need to ‘Stay Put’ but the tone was more active than before. So it was stressed that the public should ‘not attempt to join in the fight’ but noted that: ‘You have the right of every man and woman to do what you can to protect yourself, your family, and your home’. Such instructions was soon criticised for being ‘so indefinite as to be of little value’.

‘Beating the Invader’

Britain was not invaded in the summer of 1940. However this did not signal an end of the debate over how best to communicate the threat. Indeed the subject came back onto agenda in January 1941 as part of a thorough review of the government’s civil defence arrangements. The Ministry of Information were again asked to produce a leaflet which would ‘interpret and amplify’ If the Invader Comes and Stay Where You Are. The result was 15 short paragraphs that offered practical advice in a question-and-answer format. Car-owners were for the first time told to put their vehicles out of action by ‘Remov[ing the] distributer head and leads and empty[ing] the tank’.

The final leaflet was distributed in late April 1940 with the optimistic title Beating the Invader. Given what had come before, it is fitting that the delay was due to Winston Churchill’s dislike of the term ‘Stay Put’ and a disagreement with the War Office. It is similarly fitting that the leaflet was almost abandoned when concurrent attempts to ‘rouse the public’ through new posters and press advertisements was deemed to have failed. All of those involved believed that the government needed to show decisive leadership and offer clear instructions. Yet the experience of invasion publicity in the Second World War shows just how difficult it was to achieve these ends when facing a threat that many had hoped to avoid.

Further Reading

You can find out more about the history of the Ministry of Information at http://www.moidigital.ac.uk

Operation Sea Lion - Unternehmen Seelöwe

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (German: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Fall of France, Adolf Hitler, the German Führer and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, hoped the British government would seek a peace agreement and he reluctantly considered invasion only as a last resort if all other options failed. As a precondition, he specified the achievement of both air and naval superiority over the English Channel and the proposed landing sites, but the German forces did not achieve this at any point during the war and both the German High Command and Hitler himself had serious doubts about the prospects for success. A large number of barges were gathered together on the Channel coast, but, with air losses increasing, Hitler postponed Sea Lion indefinitely on 17 September 1940 and it was never put into action."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Sea_Lion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Sea_Lion#/media/File:OperationSealion.svg

German battle plan - map

https://plus.google.com/103755316640704343614/posts/W8rwrdNYq81

What if Germany Had Invaded Britain?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFpd8_-nkH8

Timewatch - Operation Sealion (BBC 1998)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ux-J8B8fURk

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/world-war-ii/new-zealand-sniper-clive_hulme.html

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-two/world-war-two-in-western-europe/operation-sealion/

http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/operation-sea-lion-hitlers-cancelled-invasion-britain-20294

MHV playlists

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK09g6gYGMvU-0x1VCF1hgA/playlists

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (German: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Fall of France, Adolf Hitler, the German Führer and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, hoped the British government would seek a peace agreement and he reluctantly considered invasion only as a last resort if all other options failed. As a precondition, he specified the achievement of both air and naval superiority over the English Channel and the proposed landing sites, but the German forces did not achieve this at any point during the war and both the German High Command and Hitler himself had serious doubts about the prospects for success. A large number of barges were gathered together on the Channel coast, but, with air losses increasing, Hitler postponed Sea Lion indefinitely on 17 September 1940 and it was never put into action."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Sea_Lion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Sea_Lion#/media/File:OperationSealion.svg

German battle plan - map

https://plus.google.com/103755316640704343614/posts/W8rwrdNYq81

What if Germany Had Invaded Britain?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFpd8_-nkH8

Timewatch - Operation Sealion (BBC 1998)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ux-J8B8fURk

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/world-war-ii/new-zealand-sniper-clive_hulme.html

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-two/world-war-two-in-western-europe/operation-sealion/

http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/operation-sea-lion-hitlers-cancelled-invasion-britain-20294

MHV playlists

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK09g6gYGMvU-0x1VCF1hgA/playlists

44-8-25 Siegfried Line Campaign 45-3-7

Battle of Germany - mfp >> .

Battle of the Bulge - mfp >> .

Siegfried Line Campaign (Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine), was a phase in the Western European Campaign of World War II.

This phase spans from the end of the Battle of Normandy, or Operation Overlord, (25 August 1944; close 30 August 1944) incorporating the German winter counter-offensive through the Ardennes (commonly known as the Battle of the Bulge) and Operation Nordwind (in Alsace and Lorraine) up to the Allies preparing to cross the Rhine in March of 1945. This roughly corresponds with the official United States military European Theater of Operations Rhineland and Ardennes-Alsace Campaigns.

Battle of the Bulge 1944 - Ardennes Counteroffensive - K&G > .

This phase spans from the end of the Battle of Normandy, or Operation Overlord, (25 August 1944; close 30 August 1944) incorporating the German winter counter-offensive through the Ardennes (commonly known as the Battle of the Bulge) and Operation Nordwind (in Alsace and Lorraine) up to the Allies preparing to cross the Rhine in March of 1945. This roughly corresponds with the official United States military European Theater of Operations Rhineland and Ardennes-Alsace Campaigns.

....

....

The Allies crossed the Rhine at four points. One crossing was an opportunity taken by U.S. forces when the Germans failed to blow up the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen; another was a hasty assault; and two crossings were planned:- The U.S. First Army aggressively pursued the disintegrating German troops, and on 7 March they unexpectedly captured the Ludendorff Bridge across the Rhine River at Remagen. The 9th Armored Division quickly expanded the bridgehead into a full scale crossing.

- Bradley told General George S. Patton—whose U.S. Third Army had been fighting through the Palatinate—to "take the Rhine on the run". The Third Army did just that on the night of 22/23 March, crossing the river with a hasty assault south of Mainz at Oppenheim.

- In the north, the Rhine is twice as wide, with a far higher volume of water than where the Americans crossed. Montgomery, commander of the 21st Army Group, decided it could be crossed safely only with a carefully prepared attack. In Operation Plunder he crossed the Rhine at Rees and Wesel on the night of 23/24 March, including the largest single drop airborne operation in history, Operation Varsity.

- In the Allied 6th Army Group area, the U.S. Seventh Army assaulted across the Rhine in the area between Mannheim and Worms on 26 March. A fifth crossing on a smaller scale was later achieved by the French First Army at Speyer.

Battle of the Bulge 1944 - Ardennes Counteroffensive - K&G > .

42-3-28 St Nazaire Raid

.

One way to do this was to cut off access to anywhere their Navy would be able to repair ships. The port of St. Nazaire in occupied France was the only port, outside Germany, large enough to repair the largest of the German Ships (like the Tirpitz). Without it, the Germans wouldn’t be able to control the Atlantic and wouldn't be able to stop the supply convoys from reaching the UK.

Putting that port out of action caused the British a dilemma. The RAF couldn’t bomb it accurately enough to destroy it, without using so many bombs that they would inflict large numbers of civilian casualties. A conventional attack from the sea was out of the question as the port was six miles up the Loire estuary and was heavily defended. The underground resistance movement and Special Operations Executive couldn’t get enough explosives into the dock to destroy it.

The only solution was a commando raid, codenamed: Operation Chariot. One that would see 87 bravery medals awarded and be described as the greatest commando raids ever.

The St Nazaire Raid or Operation Chariot was a British amphibious attack on the heavily defended Normandie dry dock at St Nazaire in German-occupied France during WW2. The operation was undertaken by the Royal Navy and British Commandos under the auspices of Combined Operations Headquarters on 28 March 1942. St Nazaire was targeted because the loss of its dry dock would force any large German warship in need of repairs, such as Tirpitz, sister ship of Bismarck, to return to home waters by running the gauntlet of the Home Fleet of the Royal Navy and other British forces, via the English Channel or the North Sea.

The obsolete destroyer HMS Campbeltown, accompanied by 18 smaller craft, crossed the English Channel to the Atlantic coast of France and was rammed into the Normandie dock gates. The ship had been packed with delayed-action explosives, well-hidden within a steel and concrete case, that detonated later that day, putting the dock out of service until 1948.

A force of commandos landed to destroy machinery and other structures. German gunfire sank, set ablaze, or immobilized virtually all the small craft intended to transport the commandos back to England. The commandos fought their way through the town to escape overland but many surrendered when they ran out of ammunition or were surrounded by the Wehrmacht defending Saint-Nazaire.

Of the 611 men who undertook the raid, 228 returned to Britain, 169 were killed and 215 became prisoners of war. German casualties included over 360 dead, some of whom were killed after the raid when Campbeltown exploded. To recognise their bravery, 89 members of the raiding party were awarded decorations, including five Victoria Crosses. After the war, St Nazaire was one of 38 battle honours awarded to the commandos. The operation has been called The Greatest Raid of All within British military circles.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

sī vīs pācem, parā bellum

igitur quī dēsīderat pācem praeparet bellum therefore, he who desires peace, let him prepare for war sī vīs pācem, parā bellum if you wan...

-

>>> Economic > >>> Geopolitics > >>> Military > >>> Resources > > >> Sociopoli...

-

2025 Fiasco; Christo-Fascist Project 2025 2025 Blueprint for Theocracy - αλλο >> . 2025 Christo-Fascist Blueprint for Autocracy - Shr...

-

> > Alliances > > > > Authoritarianism > > > Axis of Envious Resentment 2025 > > > > Civil...