1940 - USSR contribution to Nazi war-resources > .

Friday, April 26, 2019

Wednesday, April 24, 2019

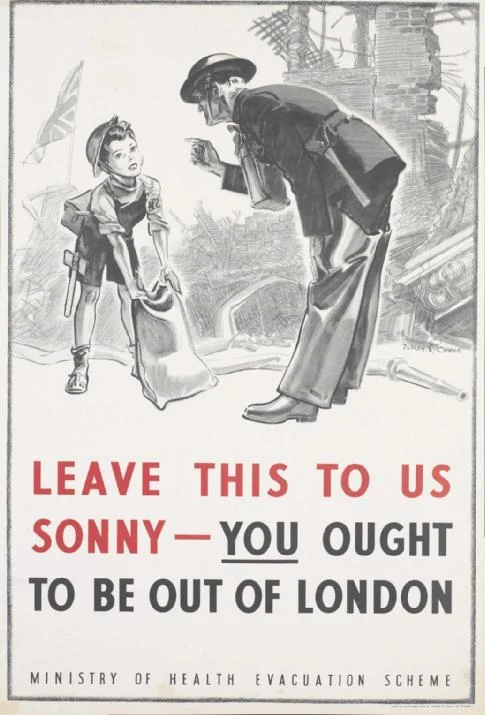

Evacuation Plans & Pied Piper

'36+ Central Government War Headquarters: '49 UK’s Secret Nuclear Bunker > .

CoG - Continuity of Government ..

Although the upper levels of government would remain in London to act as a “nucleus” the plan was to evacuate the majority of civil servants, mainly to seaside resorts that would have empty hotel accommodation. In this way for example the Ministry of Agriculture established a major presence at Colwyn Bay. This was the “yellow move”, but a last ditch “black move” was also planned should London become unusable or threatened by invasion. Under this plan the nucleus would relocate to planned accommodation in the west midlands eg the War Cabinet would move to Hindlip House near Worcester and Parliament to Stratford-upon-Avon.

.......

The initial plan was to relocate the machinery of government to the suburbs of north and northwest London. A bombproof citadel known as PADDOCK was built at Dollis Hill for the War Cabinet with supporting bunkers at Cricklewood and Harrow. The bulk of the civil servants would be accommodated in neighbouring schools and colleges left empty by evacuation.

The plan was however changed. Now, the seat of government was to remain in London for as long as possible and protected accommodation was developed. The most famous was the bunker under the New Public Buildings (also known as George Street) which was partly occupied by the Cabinet War Room. Other citadels were developed, notably the Admiralty Citadel which was in fact built illegally on part of St James’s Park and the “Rotundas” which were built off Horseferry Road in the massive holes originally dug in the previous century for gas holders. As well as these citadels a series of reinforced “steel framed buildings” were constructed in central London.

http://www.subbrit.org.uk/rsg/features/government/

https://prezi.com/7vjabhizqnei/evacuation-of-british-children-during-wwii/

The evacuation of civilians in Britain during the Second World War was designed to protect civilians in Britain, particularly children, from the risks associated with aerial bombing of cities by moving them to areas thought to be less at risk. Operation Pied Piper, which began on 1 September 1939, officially relocated more than 3.5 million people. Further waves of official evacuation and re-evacuation occurred on the south and east coasts in June 1940, when a seaborne invasion was expected, and from affected cities after the Blitz began in September 1940. There were also official evacuations from the UK to other parts of the British Empire, and many non-official evacuations within and from the UK. Other mass movements of civilians included British citizens arriving from the Channel Islands, and displaced people arriving from continental Europe.

Government functions were also evacuated. Under "Plan Yellow", some 23,000 civil servants and their paperwork were dispatched to available hotels in the better coastal resorts and spa towns. Other hotels were requisitioned and emptied for a possible last-ditch "Black Move" should London be destroyed or threatened by invasion. Under this plan, the nucleus of government would relocate to the West Midlands—the War Cabinet and ministers would move to Hindlip Hall, Bevere House and Malvern College near Worcester and Parliament to Stratford-upon-Avon. Winston Churchill was to relocate to Spetchley Park whilst King George VI and other members of the royal family would take up residence at Madresfield Court near Malvern.

Some strained areas took the children into local schools by adopting the World War I expedient of double shift education—taking twice as long but also doubling the number taught. The movement of teachers also meant that almost a million children staying home had no source of education.

......

The Government Evacuation Scheme was developed during summer 1938 by the Anderson Committee and implemented by the Ministry of Health. The country was divided into zones, classified as either "evacuation", "neutral", or "reception", with priority evacuees being moved from the major urban centres and billeted on the available private housing in more rural areas. Each zone covered roughly a third of the population, although several urban areas later bombed had not been classified for evacuation. In early 1939, the reception areas compiled lists of available housing. Space for a couple of thousand people was found, and the government also constructed camps which provided a few thousand additional spaces.

In summer 1939, the government began to publicise its plan through the local authorities. They had overestimated demand: only half of all school-aged children were moved from the urban areas instead of the expected 80%. There was enormous regional variation: as few as 15% of the children were evacuated from some urban areas, while over 60% of children were evacuated in Manchester and Belfast and Liverpool. The refusal of the central government to spend large sums on preparation also reduced the effectiveness of the plan. In the event over 1,474,000 people were evacuated.

.......

The initial plan was to relocate the machinery of government to the suburbs of north and northwest London. A bombproof citadel known as PADDOCK was built at Dollis Hill for the War Cabinet with supporting bunkers at Cricklewood and Harrow. The bulk of the civil servants would be accommodated in neighbouring schools and colleges left empty by evacuation.

The plan was however changed. Now, the seat of government was to remain in London for as long as possible and protected accommodation was developed. The most famous was the bunker under the New Public Buildings (also known as George Street) which was partly occupied by the Cabinet War Room. Other citadels were developed, notably the Admiralty Citadel which was in fact built illegally on part of St James’s Park and the “Rotundas” which were built off Horseferry Road in the massive holes originally dug in the previous century for gas holders. As well as these citadels a series of reinforced “steel framed buildings” were constructed in central London.

http://www.subbrit.org.uk/rsg/features/government/

https://prezi.com/7vjabhizqnei/evacuation-of-british-children-during-wwii/

The evacuation of civilians in Britain during the Second World War was designed to protect civilians in Britain, particularly children, from the risks associated with aerial bombing of cities by moving them to areas thought to be less at risk. Operation Pied Piper, which began on 1 September 1939, officially relocated more than 3.5 million people. Further waves of official evacuation and re-evacuation occurred on the south and east coasts in June 1940, when a seaborne invasion was expected, and from affected cities after the Blitz began in September 1940. There were also official evacuations from the UK to other parts of the British Empire, and many non-official evacuations within and from the UK. Other mass movements of civilians included British citizens arriving from the Channel Islands, and displaced people arriving from continental Europe.

Government functions were also evacuated. Under "Plan Yellow", some 23,000 civil servants and their paperwork were dispatched to available hotels in the better coastal resorts and spa towns. Other hotels were requisitioned and emptied for a possible last-ditch "Black Move" should London be destroyed or threatened by invasion. Under this plan, the nucleus of government would relocate to the West Midlands—the War Cabinet and ministers would move to Hindlip Hall, Bevere House and Malvern College near Worcester and Parliament to Stratford-upon-Avon. Winston Churchill was to relocate to Spetchley Park whilst King George VI and other members of the royal family would take up residence at Madresfield Court near Malvern.

Some strained areas took the children into local schools by adopting the World War I expedient of double shift education—taking twice as long but also doubling the number taught. The movement of teachers also meant that almost a million children staying home had no source of education.

......

The Government Evacuation Scheme was developed during summer 1938 by the Anderson Committee and implemented by the Ministry of Health. The country was divided into zones, classified as either "evacuation", "neutral", or "reception", with priority evacuees being moved from the major urban centres and billeted on the available private housing in more rural areas. Each zone covered roughly a third of the population, although several urban areas later bombed had not been classified for evacuation. In early 1939, the reception areas compiled lists of available housing. Space for a couple of thousand people was found, and the government also constructed camps which provided a few thousand additional spaces.

In summer 1939, the government began to publicise its plan through the local authorities. They had overestimated demand: only half of all school-aged children were moved from the urban areas instead of the expected 80%. There was enormous regional variation: as few as 15% of the children were evacuated from some urban areas, while over 60% of children were evacuated in Manchester and Belfast and Liverpool. The refusal of the central government to spend large sums on preparation also reduced the effectiveness of the plan. In the event over 1,474,000 people were evacuated.

Tuesday, April 23, 2019

Financing War - Economics of Defense

.

WW1 UK - War Bonds Sold From Tank (1917) - Pathé > .

24-1-24 Importance of 155mm shells - WSJ > .

24-8-13 Economics of War - CNBC I > .

2024

2022, 2023

Wartime Production - Mech >> .

In 1942, the government of Mackenzie King launch a propaganda effort that simulates Canada falling under Hitler's yoke. Why? For the war economy of course!

War finance is a branch of defense economics. The power of a military depends on its economic base and without this financial support, soldiers will not be paid, weapons and equipment cannot be manufactured and food cannot be bought. Hence, victory in war involves not only success on the battlefield but also the economic power and economic stability of a state. War finance covers a wide variety of financial measures including fiscal and monetary initiatives used in order to fund the costly expenditure of a war. Such measures can be broadly classified into three main categories:

The field revolves around finding the optimal resource allocation among defense and other functions of the government. While the primal goal is to find the optimal size of the defense budget with respect to sizes of other budgets managed by the public body, the field also studies the optimization of allocation among specific missions and outputs such as arms control, disarmament, civil defense, sealift, arms conversion, mobilization bases, or weaponry composition. At the same time, different ways these goals can be achieved are analyzed on lower levels. These consist of finding the optimal choice between alternative logistic arrangements, rifles, specialized equipment, contract provisions, base locations and so on. Since the defense management of a country consists of choosing between many substitutes, an analysis of costs and benefits of various options is vital.

Economizing in the economics of defense represents the principle of reallocating available scarce resources such that an output of the greatest possible value is produced. This can be achieved in two closely-intertwined ways:

Although the economics of defense mainly studies microeconomic topics, which involve allocation optimization and optimal choice identification, it also looks into several macroeconomic topics, which focus on the impact of defense expenditures on various macroeconomic variables such as economic growth, gross domestic product and employment.

In terms of economics, a distinctive feature of the defense is that it is public goods, and as such it is both non-excludable and non-rivalrous. As such, it may suffer the so-called "free rider problem". In the social sciences, the free-rider problem is a type of market failure that occurs when those who benefit from resources, public goods (such as public roads or hospitals), or services of a communal nature do not pay for them or under-pay. Free riders are a problem because while not paying for the good (either directly through fees or tolls or indirectly through taxes), they may continue to access or use it. Thus, the good may be under-produced, overused or degraded. Additionally, it has been shown that despite evidence that people tend to be cooperative by nature, the presence of free-riders cause this prosocial behaviour to deteriorate, perpetuating the free-rider problem.

Generally, developments in defense economics reflect current affairs. During the Cold War, the main topics included superpower arms races, establishment of strong and lasting alliances and nuclear weapon research. After the Cold War, the focus shifted to conversion opportunities, disarmament and the peace dividend availability.

Financing War - Bonds, Loans ..

Lend-Lease Act 41-3-11 ..

Lend-Lease Act 41-3-11 ..

Geostrategic Projection, 21st

European Geostrategic Projection ..- levy of taxes - Taxation

- raising of debts - Borrowing

- creation of fresh money supply - Inflation

The economics of defense or defense economics is a subfield of economics, an application of the economic theory to the issues of military defense. The formal study of economics of defense is a relatively new field. An early specialized work in the field is the RAND Corporation report The Economics of Defense in the Nuclear Age by Charles J. Hitch and Roland McKean (1960, also published as a book). It is an economic field that studies the management of government budget and its expenditure during mainly war times, but also during peace times, and its consequences on economic growth. It thus uses macroeconomic and microeconomic tools such as game theory, comparative statistics, growth theory and econometrics. It has strong ties to other subfields of economics such as public finance, economics of industrial organization, international economics, labour economics and growth economics.

Economizing in the economics of defense represents the principle of reallocating available scarce resources such that an output of the greatest possible value is produced. This can be achieved in two closely-intertwined ways:

- Improvement of the economic calculus

- Improvement of the institutional arrangements that shape defense choices

Although the economics of defense mainly studies microeconomic topics, which involve allocation optimization and optimal choice identification, it also looks into several macroeconomic topics, which focus on the impact of defense expenditures on various macroeconomic variables such as economic growth, gross domestic product and employment.

In terms of economics, a distinctive feature of the defense is that it is public goods, and as such it is both non-excludable and non-rivalrous. As such, it may suffer the so-called "free rider problem". In the social sciences, the free-rider problem is a type of market failure that occurs when those who benefit from resources, public goods (such as public roads or hospitals), or services of a communal nature do not pay for them or under-pay. Free riders are a problem because while not paying for the good (either directly through fees or tolls or indirectly through taxes), they may continue to access or use it. Thus, the good may be under-produced, overused or degraded. Additionally, it has been shown that despite evidence that people tend to be cooperative by nature, the presence of free-riders cause this prosocial behaviour to deteriorate, perpetuating the free-rider problem.

In economics, a good, service or resource are broadly assigned two fundamental characteristics; a degree of excludability and a degree of rivalry. Excludability is defined as the degree to which a good, service or resource can be limited to only paying customers, or conversely, the degree to which a supplier, producer or other managing body (e.g. a government) can prevent "free" consumption of a good.

In economics, a good is said to be rivalrous or a rival if its consumption by one consumer prevents simultaneous consumption by other consumers, or if consumption by one party reduces the ability of another party to consume it. A good is considered non-rivalrous or non-rival if, for any level of production, the cost of providing it to a marginal (additional) individual is zero. A good is "anti-rivalrous" and "inclusive" if each person benefits more when other people consume it.

A good can be placed along a continuum from rivalrous through non-rivalrous to anti-rivalrous. The distinction between rivalrous and non-rivalrous is sometimes referred to as jointness of supply or subtractable or non-subtractable.

The roots of the science of defense economics can be tracked back to the 1920s when The Political Economy of War by Arthur Cecil Pigou was originally published. While the science as such started developing in the 20th century, many of its topics can be found long before then.

A good can be placed along a continuum from rivalrous through non-rivalrous to anti-rivalrous. The distinction between rivalrous and non-rivalrous is sometimes referred to as jointness of supply or subtractable or non-subtractable.

A major step forward can be then accredited to Charles J. Hitch and Roland McKean and their work The Economics of Defense in the Nuclear Age from 1960. A great contribution to the subject came in 1975 when the British economist G. Kennedy published his book The Economics of Defence. However, importance of the field grew especially in the late 1980s and early 1990s due to political instability caused by the breakup of the Soviet Union and liberation of Eastern Europe. This resulted in the publication of a complex overview of the current state of the field in 1995 from Todd Sandler and Keith Hartley called The Handbook of Defense Economics.

Generally, developments in defense economics reflect current affairs. During the Cold War, the main topics included superpower arms races, establishment of strong and lasting alliances and nuclear weapon research. After the Cold War, the focus shifted to conversion opportunities, disarmament and the peace dividend availability.

At the beginning of the new millennium, the research shifted its attention to an increasing number of regional and ethnic conflicts (Africa, Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq), international terrorist threats (terrorist attacks on the USA) and weapons of mass destruction. Besides that, much work was dedicated to NATO, the European Union and other alliances that accepted new members and continued with developing new missions, rules and international organizations, an example being the European Security and Defence Policy, which involved the introduction of the European Defence Equipment Market and the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base.

If Day ("Si un jour", "If one day") was a simulated Nazi German invasion and occupation of the Canadian city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, and surrounding areas on 19 February 1942, during the Second World War. It was organized by the Greater Winnipeg Victory Loan organization, which was led by prominent Winnipeg businessman J. D. Perrin. The event was the largest military exercise in Winnipeg to that point.

If Day included a staged firefight between Canadian troops and volunteers dressed as German soldiers, the internment of prominent politicians, the imposition of Nazi rule, and a parade. The event was a fundraiser for the war effort: over $3 million was collected in Winnipeg on that day. Organizers believed that the fear induced by the event would help increase fundraising objectives. It was the subject of a 2006 documentary, and was included in Guy Maddin's film My Winnipeg.

War bonds are debt securities issued by a government to finance military operations and other expenditure in times of war. War bonds are either retail bonds marketed directly to the public or wholesale bonds traded on a stock market. Exhortations to buy war bonds are often accompanied by appeals to patriotism and conscience. Retail war bonds, like other retail bonds, tend to have a yield which is below that offered by the market and are often made available in a wide range of denominations to make them affordable for all citizens.

In the United Kingdom, the National Savings Movement was instrumental in raising funds for the war effort during both world wars. During World War II a War Savings Campaign was set up by the War Office to support the war effort. Local savings weeks were held which were promoted with posters with titles such as "Lend to Defend the Right to Be Free", "Save Your Way to Victory" and "War Savings Are Warships".

Canada's involvement in the Second World War began when Canada declared war on Nazi Germany on September 10, 1939, one week after the United Kingdom. Approximately half of the Canadian war cost was covered by War Savings Certificates and war bonds known as "Victory Bonds" as in World War I. War Savings Certificates began selling in May 1940 and were sold door-to-door by volunteers as well as at banks, post offices, trust companies and other authorised dealers. They matured after seven years and paid $5 for every $4 invested but individuals could not own more than $600 each in certificates. Although the effort raised $318 million in funds and was successful in financially involving millions of Canadians in the war effort, it only provided the Government of Canada with a fraction of what was needed.

The sale of Victory Bonds proved far more successful financially. There were ten wartime and one postwar Victory Bond drives. Unlike the War Savings Certificates, there was no purchase limit to Victory Bonds. The bonds were issued with maturities of between six and fourteen years with interest rates ranging from 1.5% for short-term bonds and 3% for long-term bonds and were issued in denominations of between $50 and $100,000. Canadians bought $12.5 billion worth of Victory Bonds or some $550 per capita with businesses accounting for half of all Victory Bond sales.

War-finance measures may include levy of specific taxation, increase and enlarging the scope of existing taxation, raising of compulsory and voluntary loans from the public, arranging loans from foreign sovereign states or financial institutions, and also the creation of money by the government or the central banking authority.

Loot and plunder - or at least the prospect of such - may play a role in war economies. This involves the taking of goods by force as part of a military or political victory and was used as a significant source of a revenue for the victorious state. During the first World War when the Germans occupied the Belgians, the Belgian factories were forced to produce goods for the German effort or dismantled their machinery and took it back to Germany – along with thousands and thousands of Belgian slave factory workers.

Loot and plunder - or at least the prospect of such - may play a role in war economies. This involves the taking of goods by force as part of a military or political victory and was used as a significant source of a revenue for the victorious state. During the first World War when the Germans occupied the Belgians, the Belgian factories were forced to produce goods for the German effort or dismantled their machinery and took it back to Germany – along with thousands and thousands of Belgian slave factory workers.

If Day included a staged firefight between Canadian troops and volunteers dressed as German soldiers, the internment of prominent politicians, the imposition of Nazi rule, and a parade. The event was a fundraiser for the war effort: over $3 million was collected in Winnipeg on that day. Organizers believed that the fear induced by the event would help increase fundraising objectives. It was the subject of a 2006 documentary, and was included in Guy Maddin's film My Winnipeg.

The sale of Victory Bonds proved far more successful financially. There were ten wartime and one postwar Victory Bond drives. Unlike the War Savings Certificates, there was no purchase limit to Victory Bonds. The bonds were issued with maturities of between six and fourteen years with interest rates ranging from 1.5% for short-term bonds and 3% for long-term bonds and were issued in denominations of between $50 and $100,000. Canadians bought $12.5 billion worth of Victory Bonds or some $550 per capita with businesses accounting for half of all Victory Bond sales.

The first Victory Bond issue in February 1940 met its goal of $20 million in less than 48 hours, the second issue in September 1940 reaching its goal of $30 million almost as quickly.

When it became apparent that the war would last a number of years the war bond and certificate programs were organised more formally under the National War Finance Committee in December 1941, directed initially by the president of the Bank of Montreal and subsequently by the Governor of the Bank of Canada. Under the more honed direction the committee developed strategies, propaganda and the wide recruitment of volunteers for bonds drives. Bond drives took place every six months during which no other organization was permitted to solicit the public for money. The government spent over $3 million on marketing which employed posters, direct mailing, movie trailers (including some by Walt Disney), radio commercials and full page advertisement in most major daily newspaper and weekly magazine. Realistic staged military invasions, such as the If Day scenario in Winnipeg, Manitoba, were even employed to raise awareness and shock citizens into purchasing bonds.

When it became apparent that the war would last a number of years the war bond and certificate programs were organised more formally under the National War Finance Committee in December 1941, directed initially by the president of the Bank of Montreal and subsequently by the Governor of the Bank of Canada. Under the more honed direction the committee developed strategies, propaganda and the wide recruitment of volunteers for bonds drives. Bond drives took place every six months during which no other organization was permitted to solicit the public for money. The government spent over $3 million on marketing which employed posters, direct mailing, movie trailers (including some by Walt Disney), radio commercials and full page advertisement in most major daily newspaper and weekly magazine. Realistic staged military invasions, such as the If Day scenario in Winnipeg, Manitoba, were even employed to raise awareness and shock citizens into purchasing bonds.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

sī vīs pācem, parā bellum

igitur quī dēsīderat pācem praeparet bellum therefore, he who desires peace, let him prepare for war sī vīs pācem, parā bellum if you wan...

-

>>> Economic > >>> Geopolitics > >>> Military > >>> Resources > > >> S...

-

>> Iran, XIR >> > American Imperialist Aggression - Iran - Brock >> . Iran - Tam O >> . Iran - Strikes, Crises,...

-

2026 >> America DUH Rogue >> > Assailed (by DUH), Corrupted (UN, UNWRA, ICC) - Present Tense >> . Democracy ⟺ Autho...